|

The Aftermath

General Yamanashi Hanzō, the individual appointed to direct Japan’s Martial Law Headquarters on 20 September 1923, was no stranger to demanding administrative or military tasks. Yamanashi was a seasoned soldier who had served in active combat during Japan’s previous three wars: the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, and the First World War, 1914-1918. His previous experiences did little to prepare him for the tasks he faced in post disaster Tokyo.

Overseeing restoration of political order, relief, and recovery in eastern Japan following disaster was more challenging than anyone, including Yamanashi, anticipated. Sufferers in eastern Japan were in want of everything imaginable including food, water, medical assistance, shelter, clothing, and lavatories. Most troubling to Yamanashi, however, was the fact that parts of Tokyo had descended into anarchy within hours of the disaster helping to transform a natural disaster into a human catastrophe.

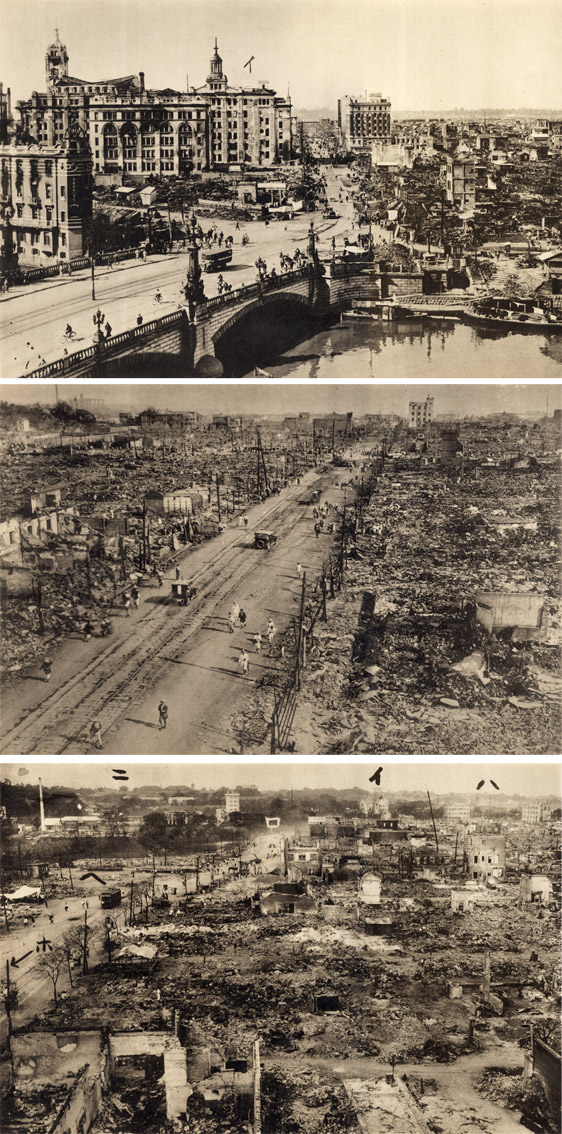

Desolation

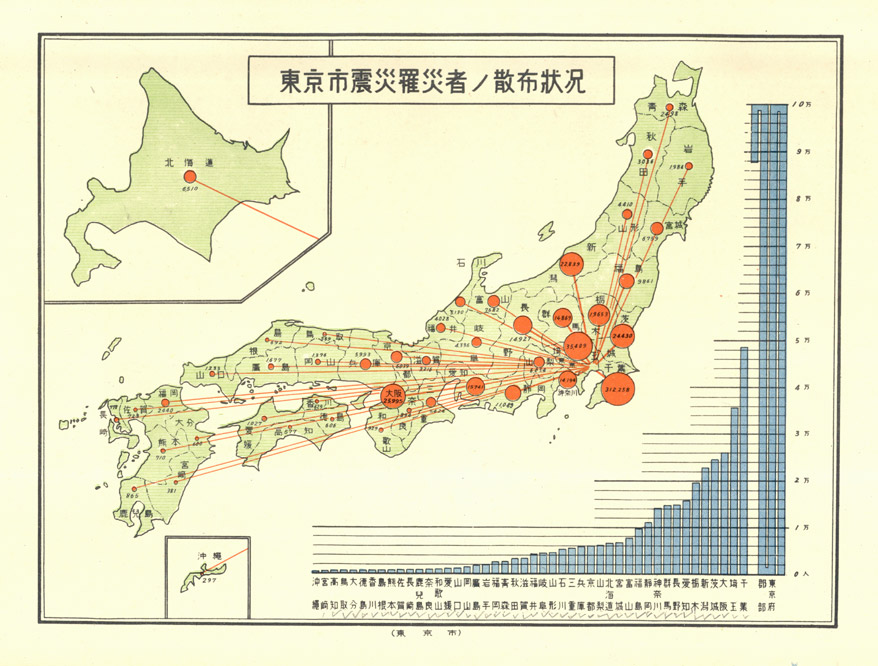

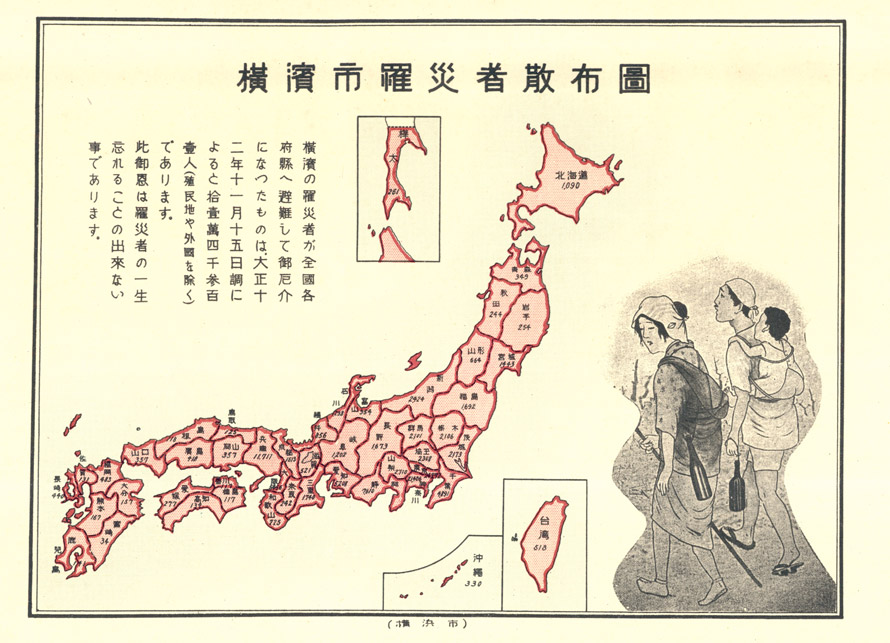

Physical desolation defined the landscape of post-disaster Tokyo. Forty-eight percent of all homes in Tokyo Prefecture (the homes of 397,119 families) were either destroyed or classified as uninhabitable as a result of the Great Kantō Earthquake and fires. Out of the City of Tokyo’s 2.26 million inhabitants, 1.38 million were rendered homeless by the disaster. In Kanagawa Prefecture, home to the city of Yokohama, 781,000 of the prefecture’s total population found themselves homeless after 1 September.

More than just destroy homes, however, the earthquake inflicted devastation across all aspects of the economy and society making any quick return to normalcy virtually impossible.

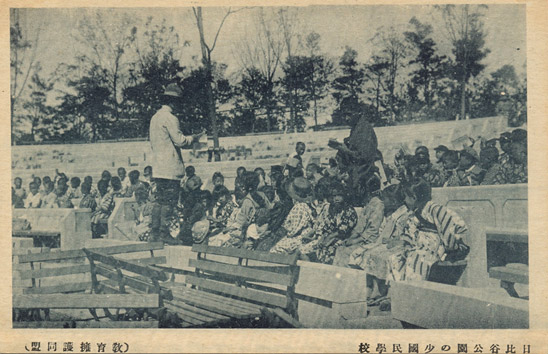

Nearly 7,000 factories met with destruction. In the City of Tokyo alone, 121 bank head offices out of a total 138 were destroyed. The meager social welfare facilities that existed to provide services to the poorest Tokyo residents were also annihilated by the disaster. 162 hospitals and 117 out of Tokyo’s 196 primary schools likewise suffered ruin. In short, the disaster left a large teeming mass of people hungry, thirsty, homeless, jobless, and often asset-less: in a word, destitute. As Takashima Beihō, a lay spokesman for the new Buddhist movement reflected, “The big city of Tokyo, the largest in the Orient at the zenith of its prosperity burned down and melted away within two days and three nights.” 33.4 million square meters of Tokyo had been turned to ash and rubble as a result of the Great Kantō Earthquake tragedy.

Rumors, Anarchy, and Murder amidst the Ruins

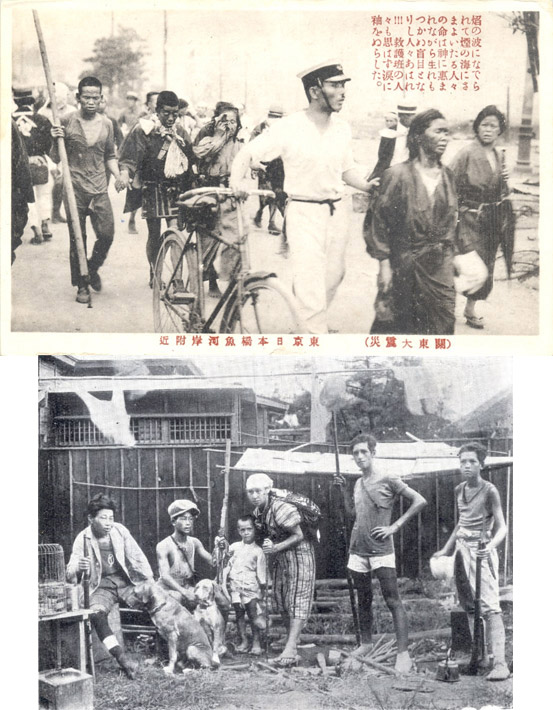

While the city burned and people evacuated, rumors began to fly like arrows. As refugews spread into neighboring wards, counties, and even prefectures, rumors of Korean duplicity surrounding the fires that engulfed Tokyo and Yokohama emerged. Tales that bands of lawless Koreans had started fires, looted shops and homes, poisoned wells, murdered women and children, and had even organized an assault on what remained of the capital found adherents. As historian Michael Weiner has illustrated, such rumors spread as far as Hokkaidō, 800km from Tokyo. While the city burned and people evacuated, rumors began to fly like arrows. As refugews spread into neighboring wards, counties, and even prefectures, rumors of Korean duplicity surrounding the fires that engulfed Tokyo and Yokohama emerged. Tales that bands of lawless Koreans had started fires, looted shops and homes, poisoned wells, murdered women and children, and had even organized an assault on what remained of the capital found adherents. As historian Michael Weiner has illustrated, such rumors spread as far as Hokkaidō, 800km from Tokyo.

Individuals and members of certain neighborhood vigilance groups [jikeidan], police and military units responded to these rumors with violence. Armed with makeshift weapons including clubs, iron pipes, swords, and bamboo spears, individuals and loosely organized bands of rabble—sometimes assisted by members of the policy and military—sought out Koreans and murdered them under the erroneous pretexts of “fire prevention” or “punishment” for the fires that many claimed Koreans had ignited. It is virtually impossible to reach any general conclusion as to why select Japanese murdered Koreans following the disaster. Racism, hatred, resentment, and criminal opportunism all contributed to this tragedy.

What is much easier to analyze, however, is how a number of commentators interpreted these murderous episodes. Writing in the Home Ministry journal Chihō gyōsei, future Minister of Commerce and Industry, Tawara Magoichi suggested that the “Korean incident” exposed a “major defect of the national spirit.” Educator Oku Hidesaburō wrote in the education journal Kyōiku, that the killing of Koreans illustrated “a moral flaw that was common among ordinary Japanese.” On the floor of Japan’s parliament—known as the Imperial Diet—MP Tabuchi Toyokichi declared that the murder of Korean was a “gross act of inhumanity” and demanded that the government “apologize to its Korean victims.” No formal apology was issued. Moreover, only 125 members of vigilance groups were prosecuted for crimes committed after the disaster. Only thirty-two received formal sentences. Two others were acquitted while ninety-one received suspended sentences.

Restoration of Order

Given the destruction, upheaval, and chaos that ensued after the disaster, the new Yamamoto Gonnohyōe cabinet declared a state of martial law over what was left of the capital on 2 September. During the following forty-eight hours, the area of martial law expanded to cover all of Tokyo, Kanagawa, Chiba, and Saitama prefectures. The government also mobilized troops from around Japan for deployment to Tokyo and Yokohama. Eventually, 52,000 troops arrived in eastern Japan to restore order, assist the relief and recovery efforts, and to repair damaged infrastructure.

Nothing prepared the soldiers—or others who ventured to Tokyo to assist with recovery—for the sights or smells that greeted them or the tasks at hand. Some of the first reports from the disaster zone read as follows: Nothing prepared the soldiers—or others who ventured to Tokyo to assist with recovery—for the sights or smells that greeted them or the tasks at hand. Some of the first reports from the disaster zone read as follows:

|

“relief aid has not yet been able to be delivered and there is a general state of anxiety amongst the population. Send more troops.”

“the extent of damage here [in Yokohama] is worse than that of Tokyo. The major institutions of the city and prefecture as well as the police have ceased to operate and wild rumors and crimes have largely unsettled the population. We wait with grateful anticipation for the arrival of more military forces.”

|

General Yamanashi later concluded that it took ten days for stability, peace, calm mindedness and public order to return. What it took in terms of manpower, he confessed, was equally extraordinary: nearly one in five members of Japan’s entire standing army had been deployed to Tokyo and Yokohama.

Relief and Recovery

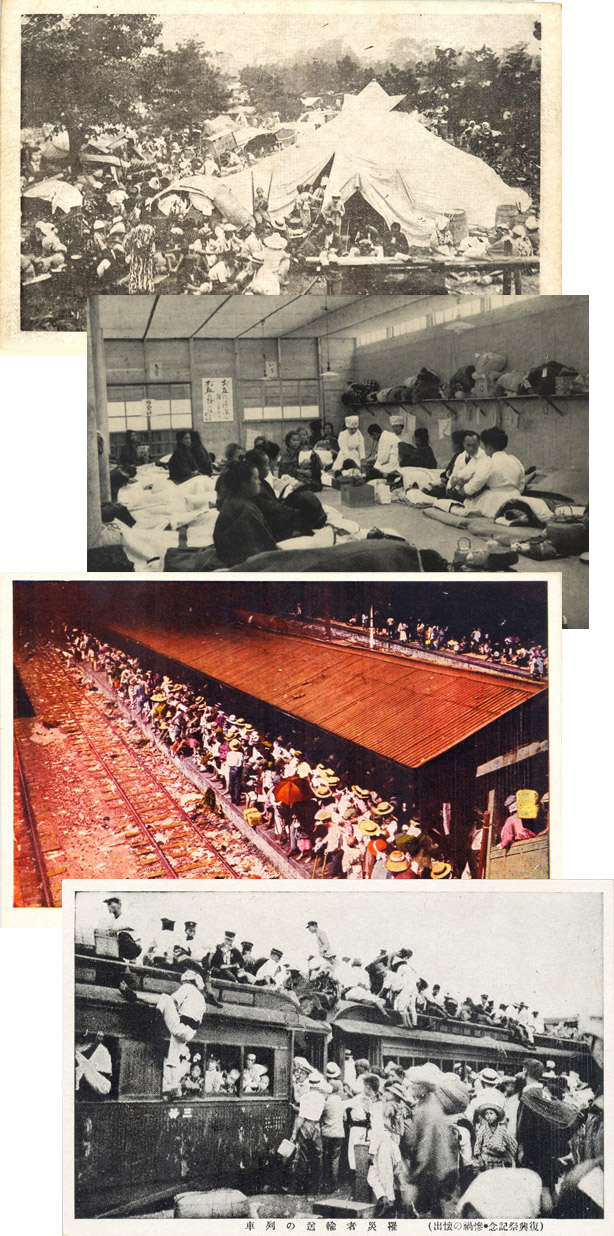

Before order had been completely restored, however, the immediate tasks of providing relief became a necessity. Providing medical assistance during the first few days following the disaster proved problematic as many hospitals, medical dispensaries, and clinics had been destroyed. Before order had been completely restored, however, the immediate tasks of providing relief became a necessity. Providing medical assistance during the first few days following the disaster proved problematic as many hospitals, medical dispensaries, and clinics had been destroyed. Moreover, the heavy damage sustained by Tokyo’s infrastructure made the transportation of donated medical supplies and medical personnel from across Japan exceedingly difficult. Moreover, the heavy damage sustained by Tokyo’s infrastructure made the transportation of donated medical supplies and medical personnel from across Japan exceedingly difficult.

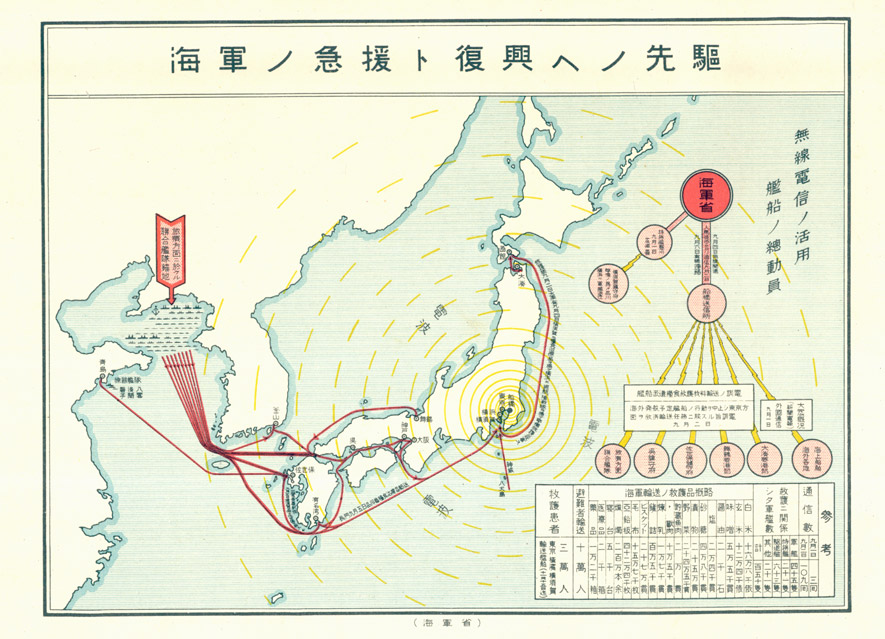

Providing clean water and food became even more of a pressing need. Initially, army and navy units across Japan amassed and then distributed nearly 120,000 combat rations from military installations in the disaster zone that had escaped destruction for civilian use. Navy vessels were also used to transport rice from military warehouses in Kobe, Osaka, Kure, and Sasebo.

Navy personnel found themselves spending the better part of one week after the disaster repairing damaged docks and rebuilding piers to accommodate relief shipments.  Army forces likewise spent considerable time repairing land-based infrastructure: they removed over 3,000 damaged rail cars and trams left derelict in Tokyo; rebuilt 85 kilometers of rail track; and constructed 27 temporary bridges across Tokyo’s rivers to facilitate the transportation of essential relief supplies. Army forces likewise spent considerable time repairing land-based infrastructure: they removed over 3,000 damaged rail cars and trams left derelict in Tokyo; rebuilt 85 kilometers of rail track; and constructed 27 temporary bridges across Tokyo’s rivers to facilitate the transportation of essential relief supplies.

From 16 to 21 September, 2,097,170 individuals received 3 go (450 grams) of rice. The last day that City of Tokyo officials distributed food to needy sufferers took place on 10 April 1924. By the end of December, 151 million litres of water had been transported to Tokyo and Yokohama for distribution. During the same period, 64 million litres of night soil had been collected from hastily built latrines and distributed to nearby farmlands.

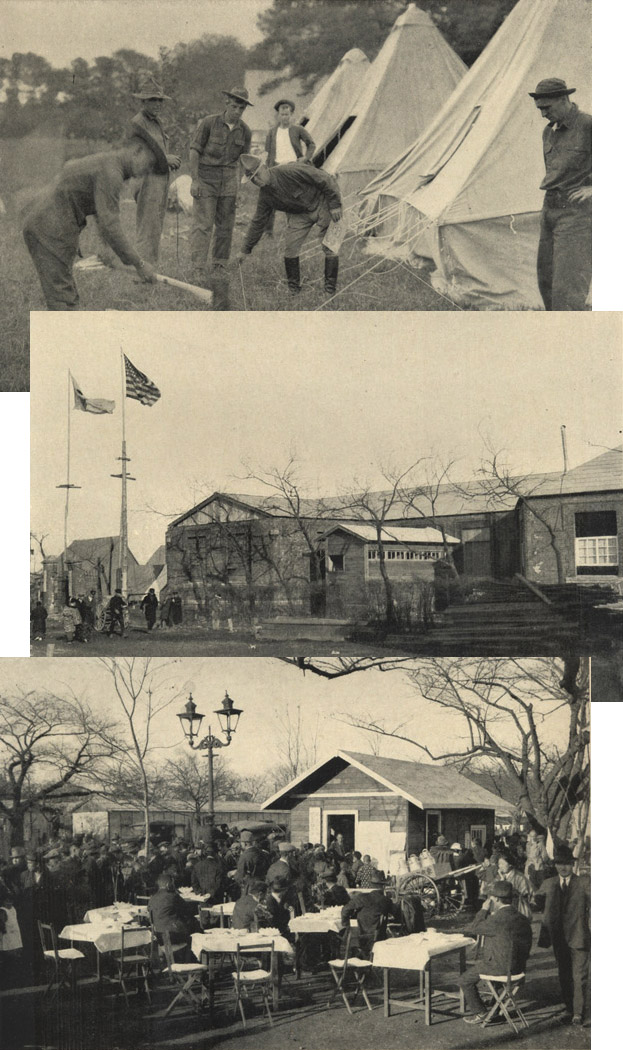

Finding housing for the displaced disaster sufferers was a longer-term problem in post-disaster Tokyo. While nearly 800,000 people evacuated Tokyo or Yokohama temporarily after the 1 September disaster, many others flocked to parks or other open spaces in the capital. Nearly 6,000 refugees established residences at the Meiji Shrine, 9,500 at Ueno Park, and 7,000 at Hibiya Park. City officials began constructing temporary barrack housing that would eventually accommodate nearly 150,000 people by 24 September. More than half a million homeless individuals returned to where their houses once stood and constructed temporary, makeshift abodes.

Viewing Tokyo in the aftermath of disaster led one foreign correspondent to write that Tokyo and Yokohama no longer resembled cities, but rather looked like shanty towns comprised of “sorry hovels”  built from “discarded sheet metal.” “It may take decades,” another wrote, for Tokyo “to rise from the ashes to its former prosperity and importance.” built from “discarded sheet metal.” “It may take decades,” another wrote, for Tokyo “to rise from the ashes to its former prosperity and importance.”

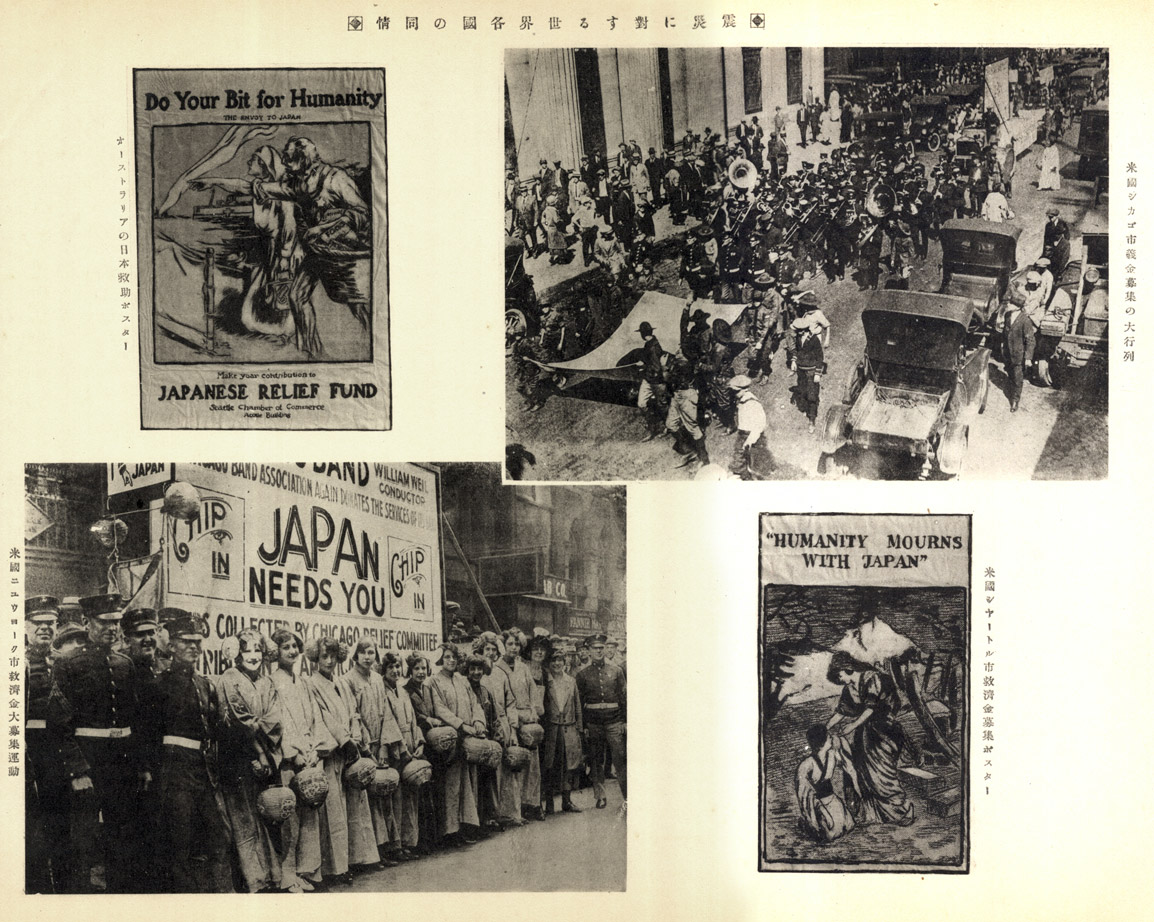

International Assistance

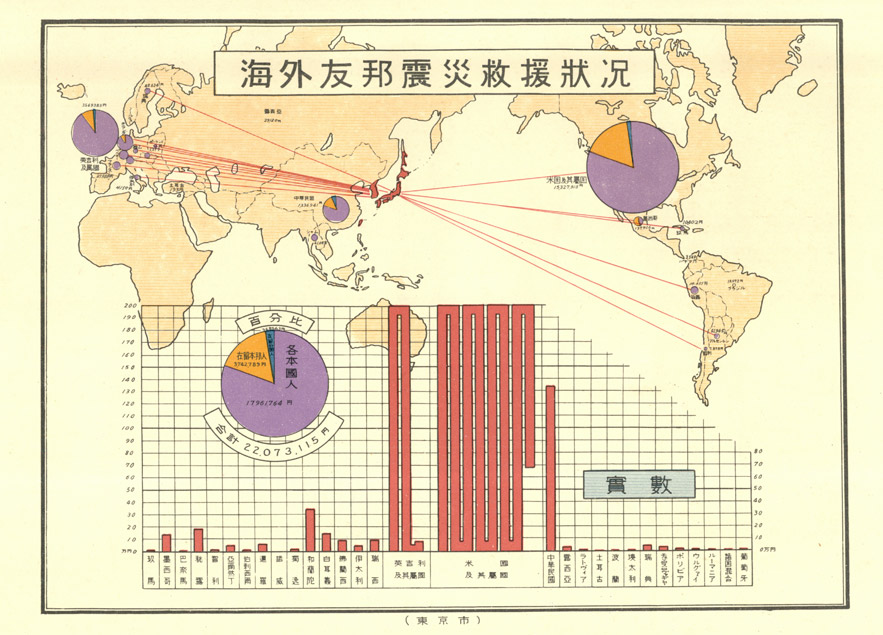

American aid following the Great Kantō Earthquake was substantial, dwarfing the contributions made by all other countries combined. Using figures published by the Japanese government, the total amount of cash contributed to Japan following the disaster amounted to roughly 22 million yen from which America provided 15.4 million yen (roughly 70 percent). Japan’s government tallied cash donations from America as follows: 12.7 million yen contributed by natives and foreign residents and 2.8 million yen by resident Japanese nationals [dōhō or zairyū hōjin]. Measuring the value of relief supplies shipped to Japan including food, blankets, tents and construction materials is much more difficult. The value of relief supplies donated by the US military was approximately $USD 9 million (7 million in supplies from the US Army and 2 million from the US Navy). Conservative estimates therefore put the total amount of cash and goods donated at about $USD 20 million, which was roughly 2.4% of America’s Gross Domestic Product. Had Americans donated the equivalent of 2.4% of its nation’s gross domestic product to the sufferers of the Indian Ocean Tsunami, they would have donated roughly 3 billion dollars; Americans in fact gave $USD 2.6 billion in relief aid to all countries affected by the 2004 tragedy. American aid following the Great Kantō Earthquake was substantial, dwarfing the contributions made by all other countries combined. Using figures published by the Japanese government, the total amount of cash contributed to Japan following the disaster amounted to roughly 22 million yen from which America provided 15.4 million yen (roughly 70 percent). Japan’s government tallied cash donations from America as follows: 12.7 million yen contributed by natives and foreign residents and 2.8 million yen by resident Japanese nationals [dōhō or zairyū hōjin]. Measuring the value of relief supplies shipped to Japan including food, blankets, tents and construction materials is much more difficult. The value of relief supplies donated by the US military was approximately $USD 9 million (7 million in supplies from the US Army and 2 million from the US Navy). Conservative estimates therefore put the total amount of cash and goods donated at about $USD 20 million, which was roughly 2.4% of America’s Gross Domestic Product. Had Americans donated the equivalent of 2.4% of its nation’s gross domestic product to the sufferers of the Indian Ocean Tsunami, they would have donated roughly 3 billion dollars; Americans in fact gave $USD 2.6 billion in relief aid to all countries affected by the 2004 tragedy.

Sources in English

Michael Allen. “The Price of Identity: The 1923 Earthquake and its Aftermath.” Korean Studies 20 (1996): 64-93.

Janet Borland. “Makeshift Schools and Education in the Ruins of Tokyo, 1923.” Japanese Studies 29:1 (May 2009): 131-143.

J. Charles Schencking. The Great Kantō Earthquake and the Chimera of National Reconstruction in Japan. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013. Chapter 2. Aftermath: The Ordeal of Restoration and Recovery.

J. Charles Schencking. “1923 Tokyo as a Devastated War and Occupation Zone: The Catastrophe One Confronted in Post Earthquake Japan.” Japanese Studies 29:1 (May 2009): 111-129.

Michael Weiner. “Koreans in the Aftermath of the Kantō Earthquake of 1923.” Immigrants and Minorities 2:1 (April 1983): 5-32.

Michael Weiner. The Origins of the Korean Community in Japan, 1910-1923. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1989. |