|

Reconstruction and Readjustment

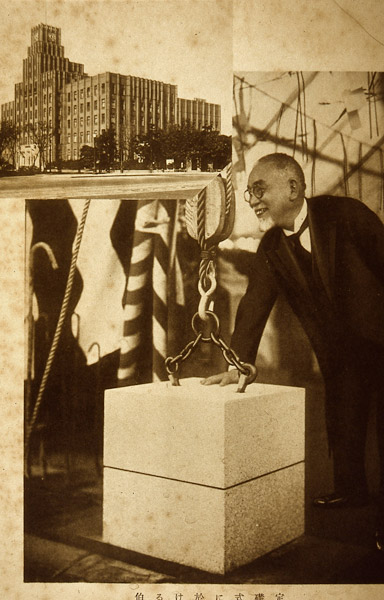

The reconstruction of Tokyo following the Great Kantō Earthquake was a monumental undertaking. Government buildings, homes, shops, roads, parks, and bridges that existed on nearly 33 million square meters of land had been destroyed. Rubble had to be cleared, lots surveyed, plans devised, and construction material sourced to rebuild a disaster-ravaged city. Amidst the ruins, however, many individuals saw an opportunity to build a city of the future. Few people epitomized this mindset better than Gotō Shinpei, former mayor of Tokyo who became Home Minister on 2 September. Gotō believed a once in a lifetime opportunity existed to build a brand new city. Within hours of assuming the position of Home Minister, Gotō informed his predecessor, Mizuno Rintarō that, “now is our best chance to completely remodel and reconstruct Tokyo.” When Mizuno cautioned Gotō that reconstruction would be expensive and politically contentious, the new Home Minister replied that people and politicians across the nation would embrace this unique chance to forge a new capital befitting the nation of Japan. Gotō predicted with no little modesty, “I will get as much money as I need.” Three months later Gotō’s optimism had vanished over the course of politically bruising and highly contentious reconstruction debates.

Optimism: Dreams for a New Tokyo

Some starry-eyed planners and bureaucrats hoped that a grandiose new capital with broad avenues and impressive government buildings could be constructed giving Tokyo a true “imperial” feel. Others advocated planning and constructing a city that would be rich in state-run social welfare infrastructure; facilities that many hoped would allow the state to better manage it subjects on social, ideological, economic, and political levels. These individuals believed that new Tokyo’s urban space and state facilities would reflect and reinforce values that the government and its reform-minded allies sought to instill among it subjects. They included health, hygiene and physical fitness, frugality, sacrifice, diligence, temperance, orderliness, and community. Other planners, citizens, and city officials wanted a city constructed with its future residents’ comforts and sensibilities in mind. Planners such as Kobashi Ichita argued for the construction of more parks, sidewalks, and green belts that could serve not only as firebreaks to avert future calamity, but also improve the quality of life for citizens on a daily basis. Still others argued for the city to be constructed with greater disaster preparedness in mind. To urban planners, social welfare advocates, and policy activists who saw the burnt our remains of Tokyo as an empty landscape of destruction, the opportunities for creation seemed endless, bound only by the limits of the imagination.

Contestation over Reconstruction

However desolate old Tokyo looked to observers in September 1923, it was not a blank slate awaiting creation. The capital of tomorrow could not be conjured into existence through innovative plans alone. Myriad property owners, shopkeepers, and families returned to where their lives once centered and sought a return to normalcy, not the beginning of a brave new metropolis. Moreover, building the city of the future would take time, money, and a concentration of political power that did not exist in 1923 Japan.

Elite-level political contestation erupted almost as soon as government officials and agencies prepared to discuss reconstruction. Planners within the Reconstruction Institute headed by Gotō Shinpei battled amongst themselves over whether to support an ideal, grandiose reconstruction plan costing upwards of 4 billion yen or one that was more moderate and likely to garner widespread national support. Cabinet members fought over whether taxes should be raised to pay for reconstruction or if this undertaking should be covered by bond issuance alone. Rural parliamentarians baulked at supporting even a scaled back reconstruction claiming that it would draw further money away from rural Japan, where people suffered year in and year out in ways not dissimilar to earthquake sufferers: on the precipice of poverty. As Miwa Ichitarō (Seiyūkai, Aichi Prefecture) declared on the floor of the parliament:

| “Sufferers of the earthquake look terrible and we feel sorry for them for sure, [but we act] as if we are shocked to see the blood of the injured. They will soon recover. I regret, however, to see that the government ignores the issues of rural areas, which may jeopardize the foundations of the nation.” |

In December 1923, parliamentarians refused to endorse even a scaled-back reconstruction bill of 598 million yen. Instead, they reduced the budget to 468 million yen. Though an additional 270 million yen was added to the reconstruction budget between 1924 and 1930, the final budget of 744 million yen for reconstruction was far less than even many of the most conservative planners hoped would be spent. The starry-eyed opportunists who believed a new grandiose imperial capital could be constructed on the ruins of Tokyo remained disillusioned throughout much of the six-year reconstruction project.

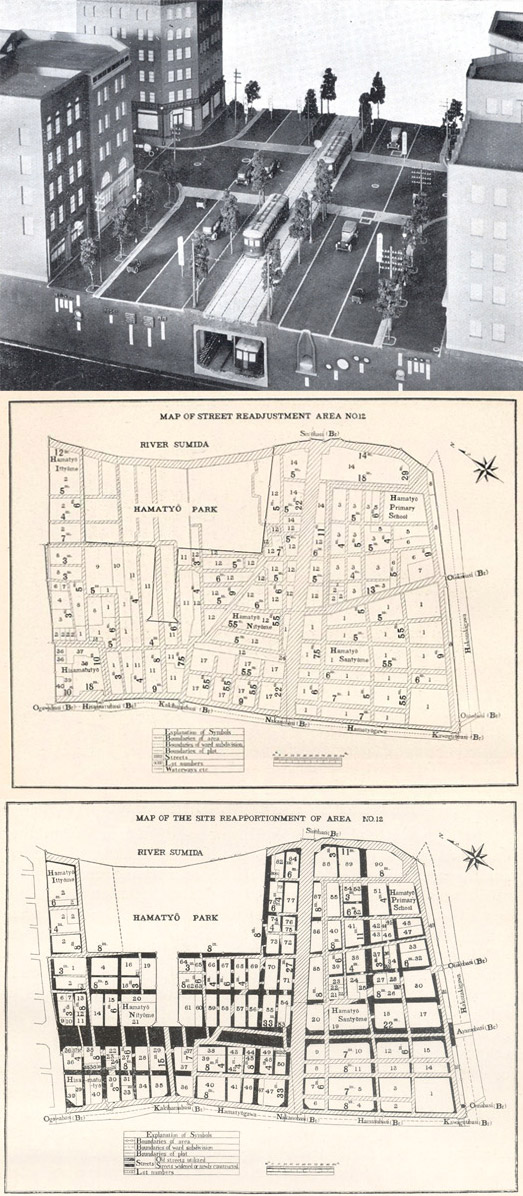

Land Readjustment: Rebuilding Tokyo from the Ashes Up

With a scaled-back reconstruction budget, city officials were forced to use a process of land readjustment [kukaku seiri] to redevelop devastated parts of the city. Under the Special Urban Planning Law promulgated by parliament on 24 December 1923, the government gained the ability to employ land readjustment to alter the boundaries of residential property lots within Tokyo. Through land readjustment, the government gained the ability to claim ten percent of everyone’s property and turn it into public space without any monetary compensation being given. With a scaled-back reconstruction budget, city officials were forced to use a process of land readjustment [kukaku seiri] to redevelop devastated parts of the city. Under the Special Urban Planning Law promulgated by parliament on 24 December 1923, the government gained the ability to employ land readjustment to alter the boundaries of residential property lots within Tokyo. Through land readjustment, the government gained the ability to claim ten percent of everyone’s property and turn it into public space without any monetary compensation being given.

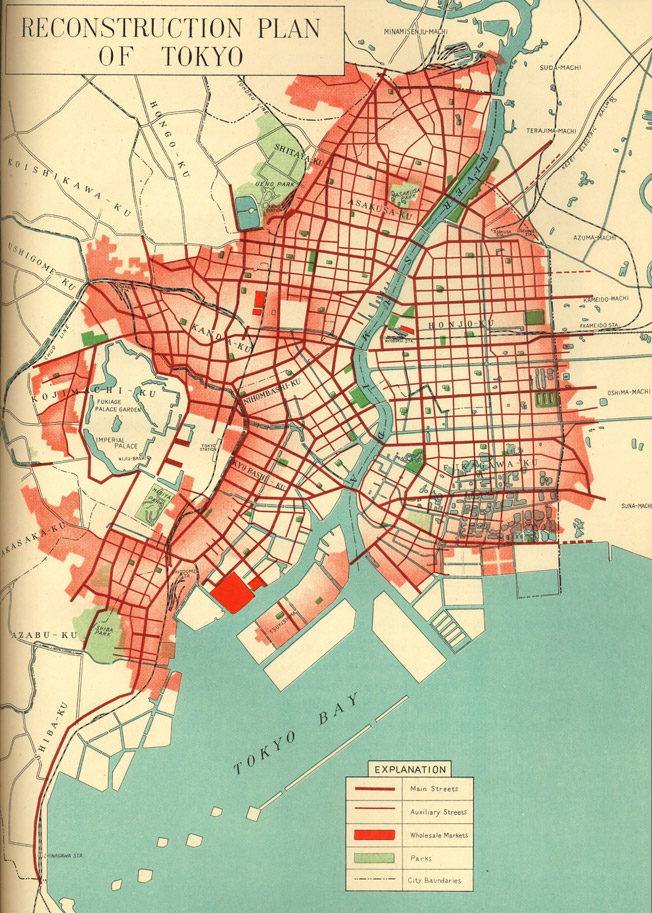

City officials divided the roughly 33 million square meters of devastated Tokyo into sixty-six Land Readjustment Districts; fifteen fell under the jurisdiction of the Home Ministry while fifty-one were administered by the City of Tokyo. Land Readjustment committees were elected in each of the sixty-six districts by landowners and business leaseholders. These committees gained influence over how individual parcels of land would be readjusted to make plots and entire neighborhoods more rational, how much compensation money was to be paid to landholders who experienced a loss of more than ten percent of their property, and the size and location of substitution lots. They also deliberated over thousands of petitions from landholders and residents over the speed, scope, and scale of readjustment.

Of the 24.9 million square meters of land that fell under the city’s readjustment jurisdiction, 18.7 million square meters were designated as residential land before readjustment. The post-readjustment total amounted to 15.8 million square meters: the total reduction of residential land stood at roughly 2.9 million square meters. Much of this land was used to build roads, sidewalks, small parks, and social welfare facilities in Tokyo.

One can see the clear rationalization that took place through land readjustment by looking at the before and after maps of Reconstruction District No.12. Directly beneath Hamachō Park (Hamatyō in the maps) a major road was created out of readjusted residential land. In many places, moreover, lots were rationalized but by no means made uniform. While few, if any individuals experienced catastrophic reduction of their land, virtually every landholder suffered major inconveniences and upheavals during the six year undertaking. More than 200,000 buildings that had been built as “temporary” structures after the disaster were forced to move—sometimes only meters, sometimes to different land plots—during this undertaking.

Sources in English

J. Charles Schencking. The Great Kantō Earthquake and the Chimera of National Reconstruction in Japan. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013. Chapter 5. Optimism: Dreams for a New Metropolis Amid a Landscape of Ruin; and, Chapter 6. Contestation: The Fractious Politics of Reconstruction Planning.

Andre Sorensen. “Urban Planning and Civil Society in Japan: Japanese Urban Planning Development During the Taishō Democracy Period (1905-1931).” Planning Perspectives 16 (2001): 383-406.

|