|

The Dead

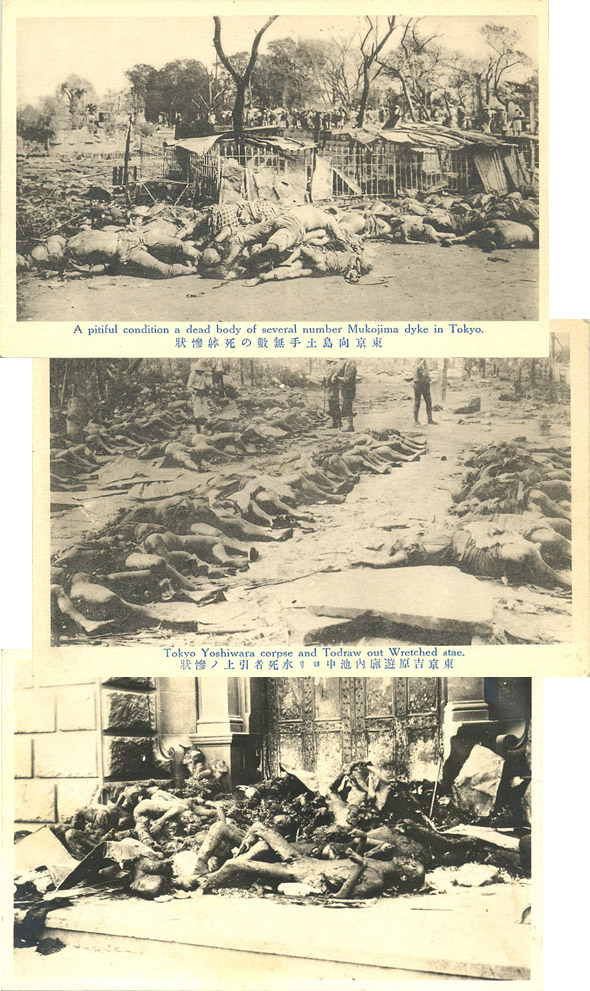

The 1923 catastrophe forced people to engage with a number of questions and issues of an interpretive and practical nature that had no precedent in modern Japanese history. Most revolved, at least initially, around the large number of civilian dead that the disaster produced. Only the Great Tenpō Famine [Tenpō no daikiken] of the 1830s killed as many civilians throughout Japan, but these deaths occurred over a longer chronological duration and larger geographical area. They thus lacked the overwhelming impact of the large numbers of dead that filled the capital in 1923. More Japanese died as a result of the Great Kantō Earthquake than perished as a result of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, and the First World War combined.

Collecting

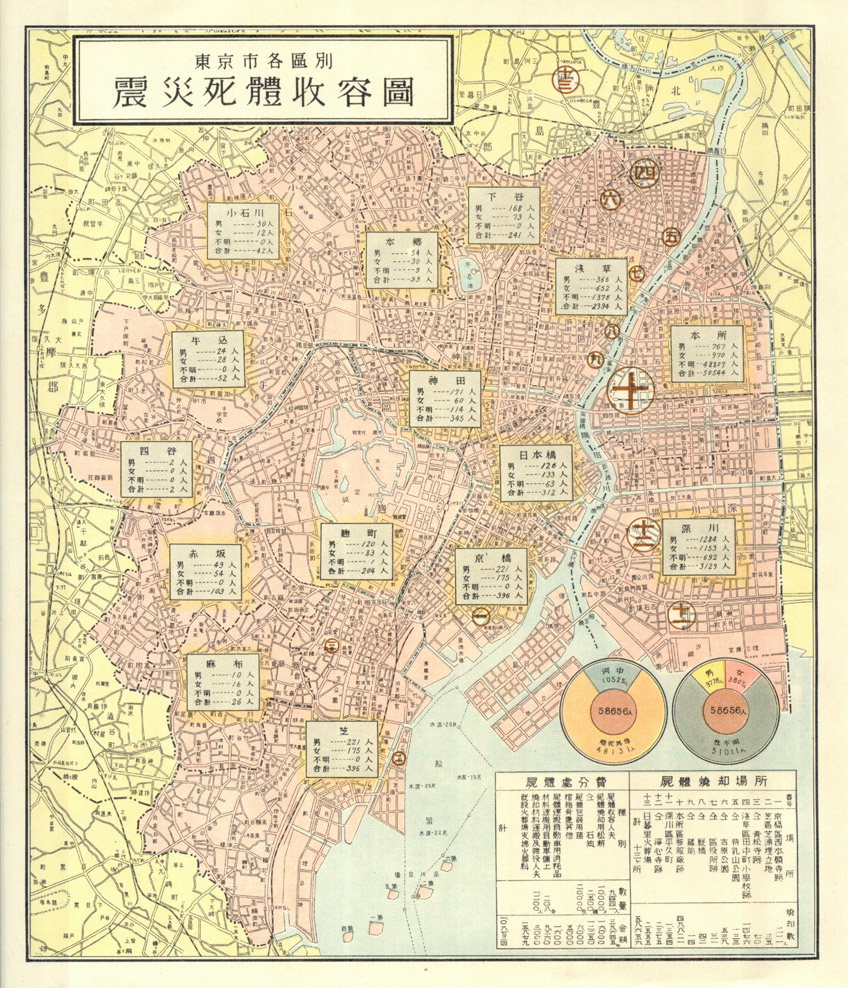

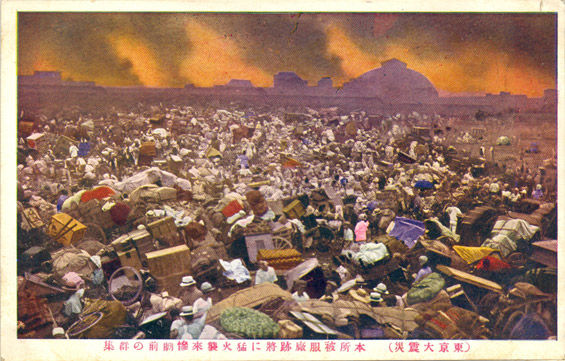

The first task associated with the dead was a practical necessity: removal from the streets, open spaces, and waterways of Tokyo. Eventually, fifteen sites across Tokyo were designated as collection centers. Over 300 city employees used motorized carts, horse-drawn wagons, and pushcarts to collect the dead. By 11 September, the Ōsaka mainichi shinbun reported that municipal officials had collected 47,200 bodies. They removed another 10,525 from Tokyo’s rivers and canals.

Documenting and Cremating

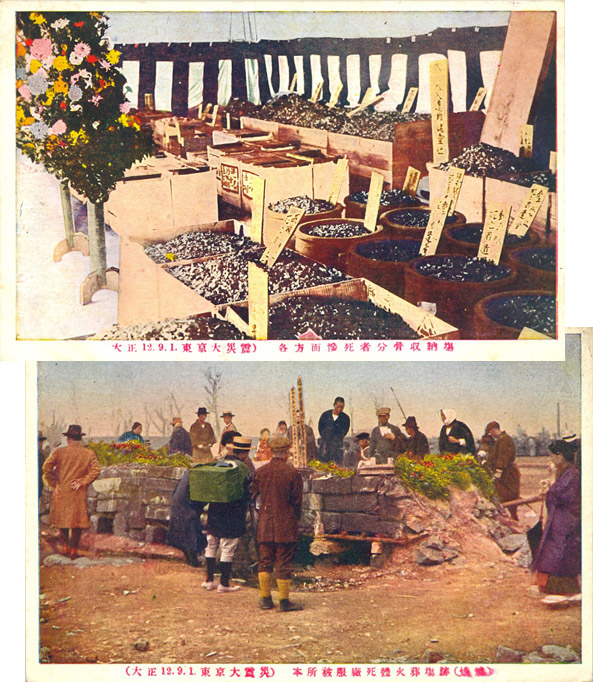

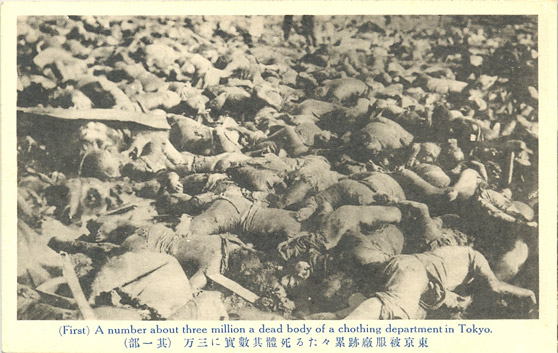

Though the city created “corpse incineration locations” [shitai shōkyaku basho], the vast majority of bodies cremated in Tokyo—roughly eighty-five percent—occurred at the site of the former Honjo Clothing Deport. Once there, a collection of city officials, police authorities, Relief Bureau workers, and Buddhist monks recorded where the bodies had come from and what day they arrived. After documenting their arrival, officials searched the bodies for any piece of personal identification or valuables. Rings, watches, and jewelry were regularly removed from the bodies. Cash, averaging about ¥10,000 per day, was also taken from the corpses and recorded. If any thieves had thought of combing the dead for money or valuables, police, Buddhist priests, and eventually the press warned against such acts of brazen, ghoulish opportunism. As one by-line in the Osaka mainichi shinbun stated: Though the city created “corpse incineration locations” [shitai shōkyaku basho], the vast majority of bodies cremated in Tokyo—roughly eighty-five percent—occurred at the site of the former Honjo Clothing Deport. Once there, a collection of city officials, police authorities, Relief Bureau workers, and Buddhist monks recorded where the bodies had come from and what day they arrived. After documenting their arrival, officials searched the bodies for any piece of personal identification or valuables. Rings, watches, and jewelry were regularly removed from the bodies. Cash, averaging about ¥10,000 per day, was also taken from the corpses and recorded. If any thieves had thought of combing the dead for money or valuables, police, Buddhist priests, and eventually the press warned against such acts of brazen, ghoulish opportunism. As one by-line in the Osaka mainichi shinbun stated:

| The cash and valuables found on those bodies is said to retain a peculiar smell which ordinary people have no means of deodorizing. Many thieves who have run away with cash or gold watches, rings, or other valuables taken from those bodies have been traced and caught on account of the unforgettable smell. |

An anonymous chronicler described the Honjo Clothing Depot as the most horrific scene he had ever witnessed; it was worse than any nightmare could ever be. Tanaka Kōtarō recorded that this site was littered with bodies, “stacked just like piles of fish that fishermen would make on shore before fish brokers came to buy them.” Eventually, Buddhist monks offered prayers for the victims and cremated the dead around the clock leaving behind large mounds of bones and ash. The haze created from the mass cremations hung over the city for weeks.

Remembering and Using

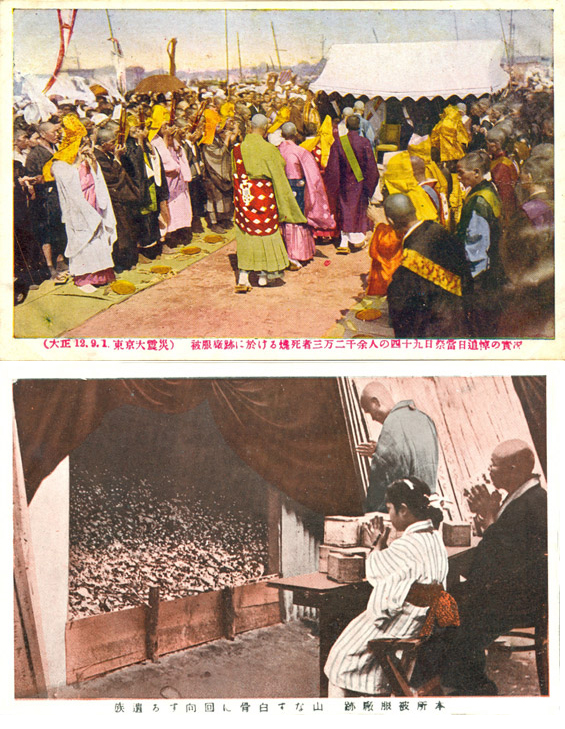

Throughout the collection and cremation process, people from across Tokyo—and from further afield—ventured to this site of death and misery. Elites such Nagata Hidejirō, Tokyo’s mayor, realized that it could become a place of extraordinary political and commemorative significance. Evoking the memory of the dead for larger political objectives became common-place at memorial and anniversary services held at this site.  At a 19 October service held forty-nine days after the calamity—a significant Buddhist memorial date to pray for the spirits of the departed—more than 200,000 citizens and virtually every major politician in Japan paid respects and spoke about the future. Many speakers declared that while it was important to mourn, they suggested it was now time for people across Japan to adopt positive actions and support far sighted policies so as to turn misfortune into a blessing. Kasuya Yoshizō, speaker of Japan’s parliament, declared: “we must not stand staring up at the heavens with tears rolling down [our] cheeks . . . what we must do is evident: unite our efforts and reconstruct the nation.” Only by doing so, he concluded, could survivors “console the spirits of the dead.” Memories of the dead and the sacrifices they gave would be evoked repeatedly at services during the seven-year reconstruction process. At a 19 October service held forty-nine days after the calamity—a significant Buddhist memorial date to pray for the spirits of the departed—more than 200,000 citizens and virtually every major politician in Japan paid respects and spoke about the future. Many speakers declared that while it was important to mourn, they suggested it was now time for people across Japan to adopt positive actions and support far sighted policies so as to turn misfortune into a blessing. Kasuya Yoshizō, speaker of Japan’s parliament, declared: “we must not stand staring up at the heavens with tears rolling down [our] cheeks . . . what we must do is evident: unite our efforts and reconstruct the nation.” Only by doing so, he concluded, could survivors “console the spirits of the dead.” Memories of the dead and the sacrifices they gave would be evoked repeatedly at services during the seven-year reconstruction process.

Sources in English

Janet Borland. “Stories of Ideal Subjects from the Great Kantō Earthquake.” Japanese Studies 25:1 (May 2005): 21-34.

Janet Borland. “Capitalizing on Catastrophe: Reinvigorating the Japanese State with Moral Values Through Education Following the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake.” Modern Asian Studies 40:4 (October 2006): 875-908.

J. Charles Schencking. The Great Kantō Earthquake and the Chimera of National Reconstruction in Japan. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013. Chapter 3. Communication: Constructing the Earthquake as a National Tragedy.

Gennifer Weisenfeld. “Imaging Calamity: Artists in the Capital After the Great Kantō Earthquake.” In Modern By, Modern Girl: Modernity in Japanese Art, 1910-1935. Edited by Jackie Menzies, 25-29. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1998.

|