|

Remembering and Commemorating

Writing in 1923, Takashima Beihō suggested that the Great Kantō Earthquake was an event that all Tokyoites would remember forever. Throughout the interwar era, politicians repeatedly evoked the memory of this disaster to support political and ideological campaigns and undertakings. Had Tokyo not suffered devastation on a similar scale in 1945 at the hands of American B-29 bombers, the Great Kantō Earthquake would have remained the single greatest collective tragedy to befall Japan’s capital.

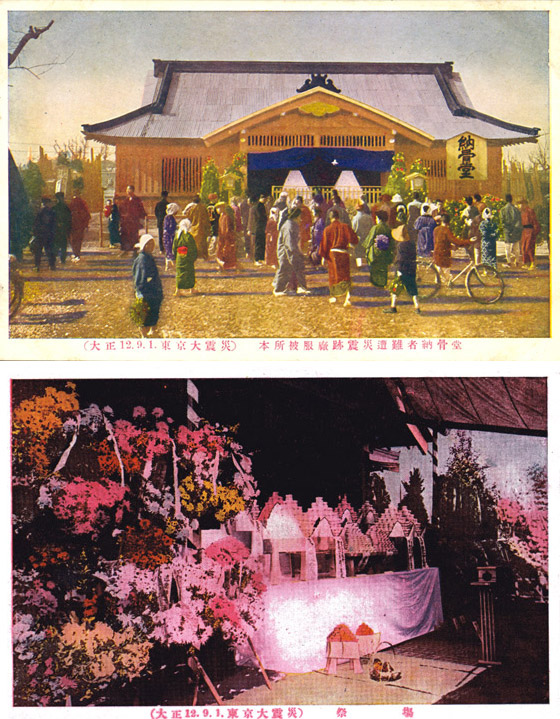

Memorial and Anniversary Services

Beginning on 21 September 1923, numerous religious, memorial, and eventually anniversary services were held at the site of the Honjo Clothing Depot. While initial services often focused on consoling the spirits of the dead and reflecting on what was lost in this terrible tragedy, over time politics and visions for the future came to permeate each ceremony. At the 49th day Buddhist ceremony held on 19 October 1923, speakers asked the people of Japan to unite behind a reconstruction program so that the “sacrifices the victims made would not go to waste.” Beginning on 21 September 1923, numerous religious, memorial, and eventually anniversary services were held at the site of the Honjo Clothing Depot. While initial services often focused on consoling the spirits of the dead and reflecting on what was lost in this terrible tragedy, over time politics and visions for the future came to permeate each ceremony. At the 49th day Buddhist ceremony held on 19 October 1923, speakers asked the people of Japan to unite behind a reconstruction program so that the “sacrifices the victims made would not go to waste.”

On the one-year anniversary of the earthquake disaster in 1924, Japan’s Prime Minister, Katō Takaaki, launched his government’s plan for national reconstruction that focused on the encouragement of thrift, diligence, and moderation. At a public address in Tokyo, Katō compelled all Japanese to “mark this day” as a “starting point” for renewal and reconstruction. On a day of solemn reflection and remembrance, Katō asked the people of Japan to end “extravagant and wasteful habits” and to willingly “share responsibility for saving the nation from its current difficulties.” Local and national politicians continued to use anniversary services for political purposes throughout the reconstruction process and well into the interwar decades. In 1960 the Japanese government declared the anniversary of the Great Kantō Earthquake as Disaster Prevention Day.

The Earthquake Memorial Hall

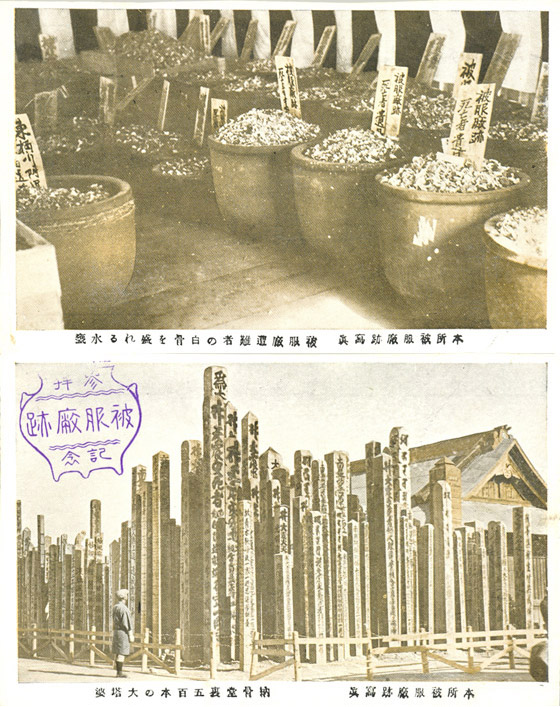

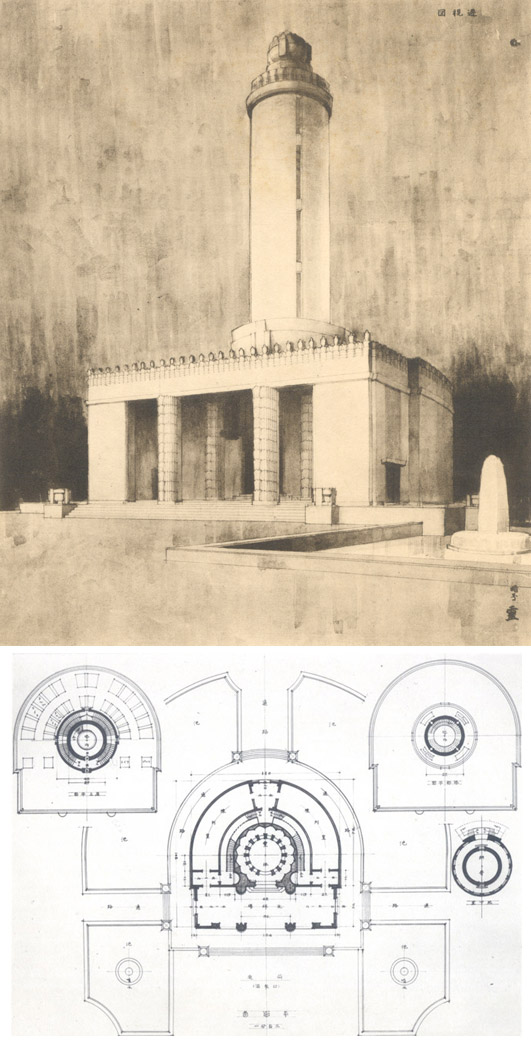

In June 1924, the municipal government created the institution known as the Taishō Earthquake Disaster Memorial Project Association to oversee the construction of an earthquake memorial. The site of the Honjo Clothing Depot was selected to house the monument and a national competition was launched to select the design of the memorial hall. Committee members set a deadline of 28 February 1925 for the contest and by its close, 220 engineers and architects from across Japan had submitted designs. For two weeks, seven judges deliberated over the submission. In March 1925, Maeda Kenjirō’s design was awarded first place. In June 1924, the municipal government created the institution known as the Taishō Earthquake Disaster Memorial Project Association to oversee the construction of an earthquake memorial. The site of the Honjo Clothing Depot was selected to house the monument and a national competition was launched to select the design of the memorial hall. Committee members set a deadline of 28 February 1925 for the contest and by its close, 220 engineers and architects from across Japan had submitted designs. For two weeks, seven judges deliberated over the submission. In March 1925, Maeda Kenjirō’s design was awarded first place.

Maeda’s winning design featured a 53-meter high tower with a diameter of 8.8 meters. Made of reinforced concrete, the tower was an impressive design that included ten stories and a basement measuring 1,093 square meters in total space. Directly above the charnel house and in the middle of the large tower, Maeda placed a sacred white marble pillar that would represent the spirits of the dead.

When the design was displayed to the public at the Tokyo Municipal Hall in Ueno Park from 21 to 23 March, 1925, it took only days for cries of protest and disgust to filter back to the Memorial Association judges. Some claimed the building was too “western” in appearance. Others claimed it was a reproduction of a Prussian triumphal tower. Still others argued that Maeda’s design did not conform to people’s religious or spiritual values. The Japan Buddhist Federation took the lead role in fomenting dissent against the planned memorial hall design and collected signatures on petitions that requested a new design be selected. They were joined by a number of local politicians from Honjo Ward. Eventually, the Memorial Association judges agreed to jettison Maeda’s design and under the direction of Itō Chūta, created a design that appealed to Buddhists and residents alike. It stands in Tokyo today. When the design was displayed to the public at the Tokyo Municipal Hall in Ueno Park from 21 to 23 March, 1925, it took only days for cries of protest and disgust to filter back to the Memorial Association judges. Some claimed the building was too “western” in appearance. Others claimed it was a reproduction of a Prussian triumphal tower. Still others argued that Maeda’s design did not conform to people’s religious or spiritual values. The Japan Buddhist Federation took the lead role in fomenting dissent against the planned memorial hall design and collected signatures on petitions that requested a new design be selected. They were joined by a number of local politicians from Honjo Ward. Eventually, the Memorial Association judges agreed to jettison Maeda’s design and under the direction of Itō Chūta, created a design that appealed to Buddhists and residents alike. It stands in Tokyo today.

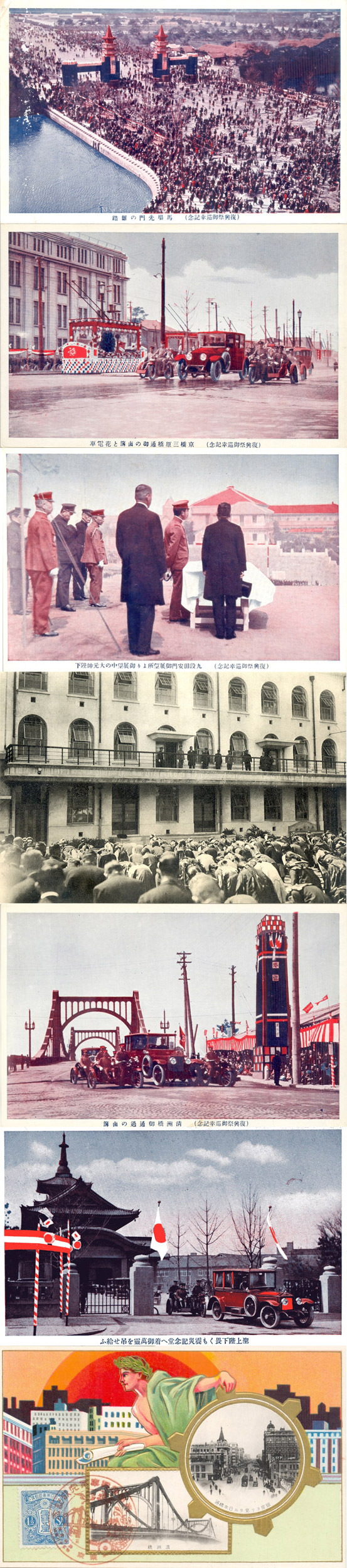

New Tokyo and the 1930 Celebration

On 24 March 1930, more than a million Tokyoites participated in the opening act of what became a weeklong series of events held to celebrate Tokyo’s rebirth. A highlight of the celebrations was a 35 km tour of the city conducted by the Shōwa Emperor. The emperor’s motorcade traversed the Sumida River over four of the six new bridges heralded as great engineering achievements and exemplars of architectural modernity. The avenues selected for the tour were the widest, most magisterial streets in Tokyo including Shōwa dōri, Yasukuni dōri, Asakusa dōri, Kiyosumi dōri, Eitai dōri, and Hibiya dōri. The emperor also visited Chiyoda Primary School, and parks including Sumida and Hamachō. On 24 March 1930, more than a million Tokyoites participated in the opening act of what became a weeklong series of events held to celebrate Tokyo’s rebirth. A highlight of the celebrations was a 35 km tour of the city conducted by the Shōwa Emperor. The emperor’s motorcade traversed the Sumida River over four of the six new bridges heralded as great engineering achievements and exemplars of architectural modernity. The avenues selected for the tour were the widest, most magisterial streets in Tokyo including Shōwa dōri, Yasukuni dōri, Asakusa dōri, Kiyosumi dōri, Eitai dōri, and Hibiya dōri. The emperor also visited Chiyoda Primary School, and parks including Sumida and Hamachō.

In many ways, these sites were representative of where money was spent on reconstruction. Out of the total 744 million yen appropriated between 1924 and 1930, 488 million (or roughly sixty-six percent) was spent on roads, canals, bridges, and the process of land readjustment. Far less was spent on social welfare facilities (4.5 million yen or roughly 0.6% of the total reconstruction budget) than many hoped. Horikiri Zenjirō, Tokyo’s Mayor in 1930, reflected on this fact when he declared, “the reconstruction plan completed today is much smaller than Mr. Gotō intended.”

People who experience a megadisaster such as the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake and those who interpret and construct such occurrences often believe that a catastrophic event of this magnitude will change everything. Rarely, however, if history serves as a judge, have disasters imparted change in societies, behaviors, or systems in such a sweeping manner. Anthropologists, social scientists, and historians who have examined disasters and the reconstruction processes that follow have found numerous instances in which the contestation, resistance, and resilience—not to mention competing visions of what should be reconstructed and how—replace the optimism and opportunism that often spring forth from devastated, post-disaster landscapes. This was certainly true of Japan following the Great Kantō Earthquake.

Sources in English

J. Charles Schencking. The Great Kantō Earthquake and the Chimera of National Reconstruction in Japan. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013. Chapter 8. Readjustment: Reconstructing Tokyo from the Ashes.

|