|

Reflections and Interpretations

Across time and cultures "natural disasters" have compelled reflection. They have also been described, explained and interpreted repeatedly as acts of heaven, the gods, or supernatural forces beyond the control of man. Japan's myths—as well as those from other earthquake prone regions—are studded with references to calamities originating from realms beyond the domain of everyday man.

Natural disasters have also been used frequently by elites for political, ideological, or economic purposes. The Great Kantō Earthquake is one case in point. Many Japanese bureaucrats, politicians, religious leaders, social commentators, and journalists publicly described the earthquake as divine punishment for clear political and ideological purposes. They sought to strengthen previously expressed concerns about, and highlight displeasure with what they saw in 1920s urban Japan, namely decadence, selfishness, extravagance, frivolity, individualism, and the pursuit of luxury. In essence these critiques were based on concerns about the perceived state of urban modernity in Japan. Numerous individuals felt that Japanese people had jettisoned the Meiji-era values of sacrifice, loyalty, selflessness, frugality, and obedience. While such concerns were not new, the earthquake significantly increased the cacophony of alarmist voices in Japan, amplified the resonance of their calls, and gave perceived cosmological “legitimacy” to concerns about the moral degradation of Japanese society.

Constructing and Disseminating the Catastrophe

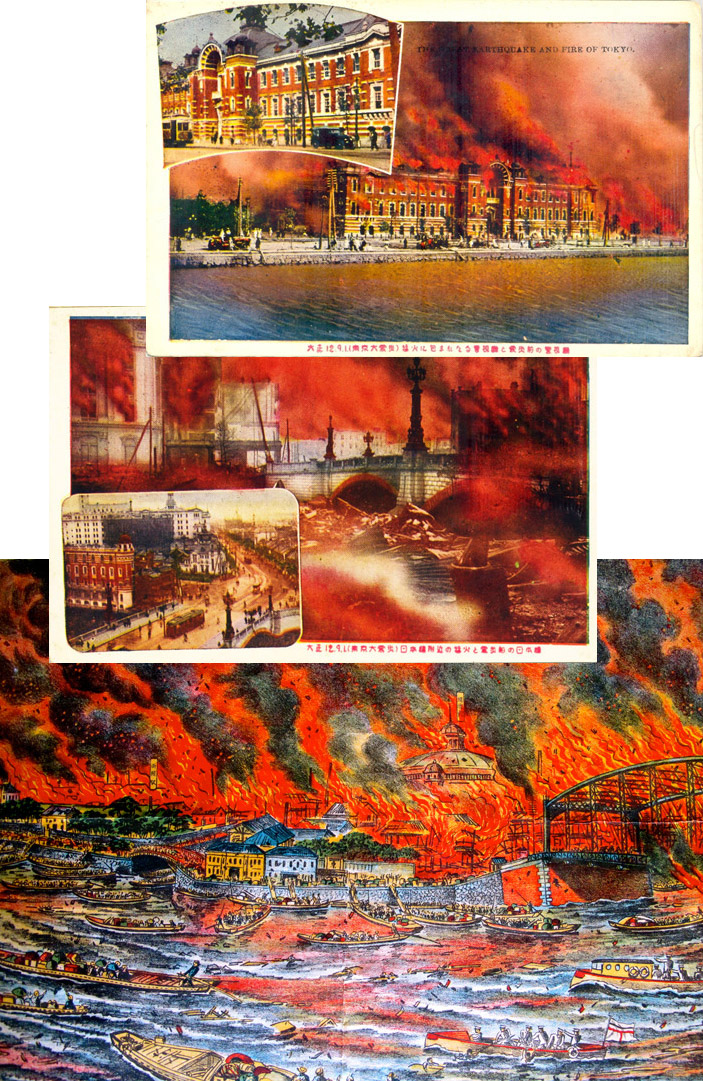

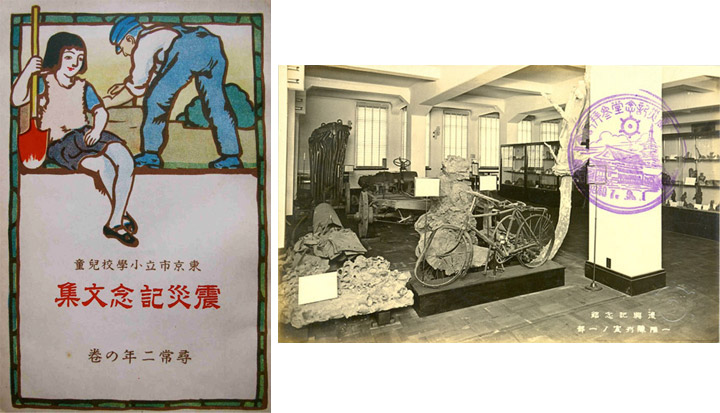

Before individuals used the disaster to admonish Japanese urbanities, a process of disaster construction and dissemination had begun in earnest. Individuals, organizations, and governmental agencies used various media to relay many aspects of the Great Kantō Earthquake tragedy to people around the nation. Created and disseminated for a multitude of reasons, artwork, postcards, and other emotive images of the tragedy helped create a rich visual culture of catastrophe. Earthquake-related visual material was produced both by recognized artists and by anonymous individuals who wished to capture a specific aspect of the unfolding tragedy or its aftermath. Some items were created purposely with the intent of enriching their creator monetarily, while other items were forged simply to record some part of the catastrophe for posterity. Though most visual images were created with a domestic audience in mind, postcards with captions translated into rudimentary English were crafted by individuals clearly cognizant of a larger market beyond those fluent in Japanese. Before individuals used the disaster to admonish Japanese urbanities, a process of disaster construction and dissemination had begun in earnest. Individuals, organizations, and governmental agencies used various media to relay many aspects of the Great Kantō Earthquake tragedy to people around the nation. Created and disseminated for a multitude of reasons, artwork, postcards, and other emotive images of the tragedy helped create a rich visual culture of catastrophe. Earthquake-related visual material was produced both by recognized artists and by anonymous individuals who wished to capture a specific aspect of the unfolding tragedy or its aftermath. Some items were created purposely with the intent of enriching their creator monetarily, while other items were forged simply to record some part of the catastrophe for posterity. Though most visual images were created with a domestic audience in mind, postcards with captions translated into rudimentary English were crafted by individuals clearly cognizant of a larger market beyond those fluent in Japanese.

Whether people across Japan learned about the disaster through photos published in newspaper, newsreels (katsudō shashin), picture post cards, lithographic prints (sekiban), or drawings, visual imagery compelled viewers to engage with the scale and severity of Japan’s calamity in ways that published survivor accounts or newspaper stories could not: they stirred emotions through sight. Whether people across Japan learned about the disaster through photos published in newspaper, newsreels (katsudō shashin), picture post cards, lithographic prints (sekiban), or drawings, visual imagery compelled viewers to engage with the scale and severity of Japan’s calamity in ways that published survivor accounts or newspaper stories could not: they stirred emotions through sight.

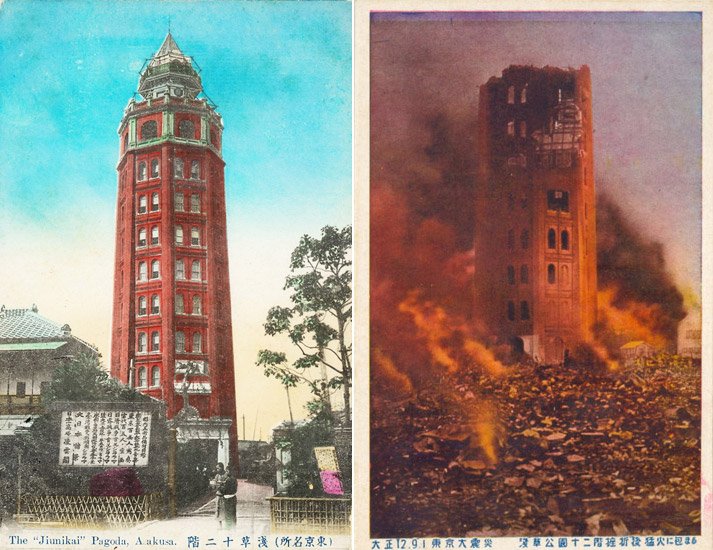

Lithograph prints depicting the catastrophe were one medium through which people across Japan learned of the disaster. Mass produced in quick fashion in the days and weeks following the disaster, these prints are striking for both the vivid colors employed and for the scenes and subjects portrayed. One image shown to the right illustrates Tokyo engulfed in flames and the Sumida River packed with people in boats trying to flee the landscape of suffering. Others depicted the tragedy of the whirlwind firestorm that swept through Honjo, the spread of fires around the twelve-storey tower in Asakusa Park and Hanayashiki, and the imperial tour that inspected the ruins of Tokyo from a lookout in Ueno Park on 15 September 1923.

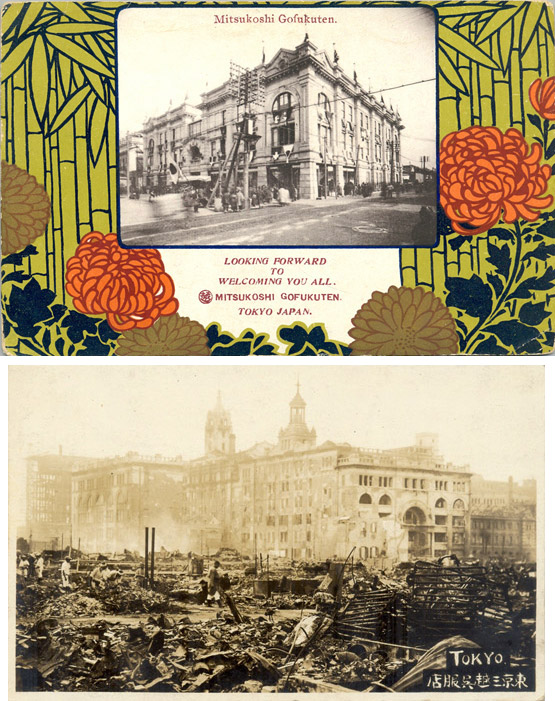

The most common way people across Japan gained visual insight into the scale of destruction Tokyo experienced was through the medium of picture postcards. Many postcards were published in series that began with images of important buildings, landmarks, or famous scenes and places in Tokyo before the catastrophe.  After these images, the postcard series often included one or two cards that portrayed scores of panic-stricken individuals fleeing Tokyo. Often, producers enhanced pictures of approaching flames with brightly coloured ink to dramatize their subject matter. To highlight what was lost in the earthquake and fires, numerous cards depicted before and after scenes of the devastated landscape. Finally, postcards also depicted images of the dead; at the site of Honjo Clothing Depot; in front of famous landmarks such as Manseibashi Train Station; on the streets of Nihonbashi, or in the brothel district of Yoshiwara. After these images, the postcard series often included one or two cards that portrayed scores of panic-stricken individuals fleeing Tokyo. Often, producers enhanced pictures of approaching flames with brightly coloured ink to dramatize their subject matter. To highlight what was lost in the earthquake and fires, numerous cards depicted before and after scenes of the devastated landscape. Finally, postcards also depicted images of the dead; at the site of Honjo Clothing Depot; in front of famous landmarks such as Manseibashi Train Station; on the streets of Nihonbashi, or in the brothel district of Yoshiwara.

Apart from visual images, Japanese also learned of the tragedy through newspaper accounts, published compilations of beautiful tales from the tragedy (bidan), and even through traveling catastrophe road shows that brought items, images, stories,and motion pictures of the tragedy to viewers across Japan.

Heavenly Punishment

In the aftermath of the 1923 calamity, numerous commentators and average Tokyoites asked a simple question: why? Why had the disaster struck? Why did areas of Tokyo known as the entertainment districts (Asakusa, Yoshiwara), consumer districts (Ginza, Nihonbashi), and slum areas (Fukagawa, Honjo) bear the brunt of destruction? Was there a meaning behind the calamity? More than a few individuals believed so. Many described the disaster as an act of heavenly punishment (tenken or tenbatsu) or divine warning. Reflecting on this trend in society, Shitennō Nobutaka wrote in the Home Ministry journal Chihō gyōsei, that “the divine punishment theory” was felt “acutely” across society immediately following the catastrophe.

Admonishment and Blame

Many commentators used the disaster to critique trends and developments in society that they did not like as bringers of heavenly punishment. Yamada Yoshio, professor of philology and literature at Tohoku University, wrote that “this was a disaster they [the people of Japan] had brought on themselves.” Some Japanese such as General Ugaki Kazushige suggested that Japan had become too materialistic, consumer-oriented and capitalistic since the end of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905. Tenrikyō Priest Okutani Fumitomo suggested that the gods had destroyed the consumer areas of the Ginza and Nihonbashi, “where crowds had flocked to satisfy their vanity” as an awakening call to encourage Tokyoites to end their slavish devotion to luxury-oriented consumerism. The destruction of Mitsukoshi Department store, pictured above, was often highlighted as a sign of heaven’s displeasure with increasing consumerism.

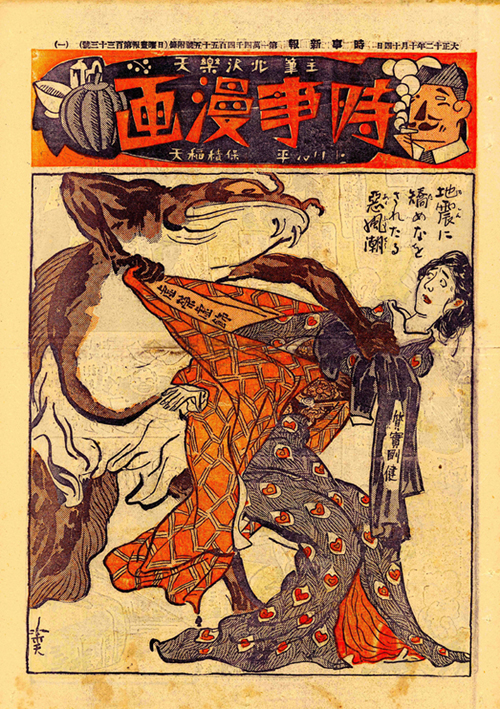

Women, particularly city dwellers who challenged stereotypes of idealized subjects, were viewed by many commentators as those in society most responsible for bringing about the act of divine punishment on 1 September 1923. This is depicted all too well in an image produced by Kitazawa Rakuten and published on the cover of the magazine Jiji manga, on 14 October 1923. In this print, Kitazawa placed an aggressive catfish (the creature in Japanese folklore metaphorically associated with the cause of earthquakes) with human arms thrusting a black cloak with the words shitsujitsu gōken [fortitude and earnestness] on a gaily dressed woman. At the same time, the catfish is tearing away a layer of clothing marked with the words kyoei kyoshoku [vanity and ostentation]. Entitled the “Catfish Rectifies the Evil Trends in Society” the print also alludes to the sexual dimension of degeneration that many elites articulated. Numerous commentators saw women not only as the primary consumers of expensive, frivolous, and ostentatious luxury items but also as the personification of lustful, carefree frivolity that many suggested defined the age.

Economist Horie Ki’ichi pointed out that it was not just the consumer areas that had been destroyed, but also the entertainment districts such as Asakusa. In Asakusa, many commentators suggested, people wasted time and money on hedonistic, frivolous, and idle pursuits. Like Mitsukoshi Department Store, the destruction of the twelve-storey tower of Asakusa, also pictured, was often employed to demonstrate heaven’s displeasure with this aspect of modern urban life.

The Great Kantō Earthquake was a unique, seemingly apocalyptic, and in many ways galvanizing event. It allowed a diverse group of social commentators to consolidate around a meta narrative of catastrophe that drew on and reinforced their opinions that Japan was mired in a state of degeneration.

Sources in English

J. Charles Schencking. The Great Kantō Earthquake and the Chimera of National Reconstruction in Japan. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013. Chapter 4. Admonishment: Interpreting Catastrophe as Divine Punishment; and Chapter 7. Regeneration: Forging a New Japan Through Spiritual Renewal and Fiscal Retrenchment.

J. Charles Schencking. “The Great Kantō Earthquake and the Culture of Catastrophe and Reconstruction in 1920s Japan.” Journal of Japanese Studies 34:2 (Summer 2008): 294-334.

Gregory Smits. “Shaking Up Japan: Edo Society and the 1855 Catfish Prints.” Journal of Social History 39:4 (Summer 2006): 1045-1077.

|